The revolutionary advance [is] made headway not by its immediate tragic-comic achievements, but on the contrary by the creation of a powerful, united counter-revolution, by the creation of an opponent, by the fighting of which the party of revolt first ripened into a real revolutionary party. —Karl Marx

In the past three years masses of Syrians have engaged in undermining the regime’s legitimacy, they have done this from physical places—squares, churches, mosques, campuses—and virtual spaces—the countless online agora’s facilitated by the Internet. A key issue raised by this paper is what happens when these spaces are no longer the "unique" let alone privileged property of the non-elites? What happens when the state, its institutional forces, and its informal gatekeepers lay claim to the same spaces and mobilize through equivalent virtual zones?

Some of the Syrian examples I have come across reminded me of the Israeli propaganda campaigns, commonly known as "hasbara," which I study in another research project with regards to Israeli cyber warfare tactics. The analogy is not meant to conflate Syria and Israel but should be considered simply as a way to accentuate the dynamics of (hegemonic) mediation in the context of digital media and a dynamic that is structured beyond commercial hiring of public relation experts, that suggest a subtler (yet paradoxical) phenomenon. These counter-revolutionary troupes are encouraged by the regime: some are passive supporters while others actively engage in a voluntary manner. Subsequently, they tend to accept (though not necessarily relish) compromising the collective rights of fellow Syrians and the subordination of their own principles in the process.

In the end however the regime’s gatekeepers and propagandists harm Syrian revolutionaries in overt and covert ways. This paradox is most clear where—aside from self-interest motivated by protection of social or economic capital tied to the regime—the common motive can be explained as acts that stem from the belief they are performing “anti-imperial resistance.”

How is it that, especially in Syria, while they initially gained some, local activists seem to have lost a great deal as well? Syrian activists who joined along with the Arab revolutions like falling dominoes subsequently faced hostile multitudes and countless confrontations often from different sides at once. In this highly contentious set of interactions, the bitter truth is that these sharp contradictions do not reflect an abnormality but rather a revolutionary normality. Marx produced some of the most illuminating writings of the revolutionary paradox that help us to begin to find answers to this paradox. He counterposes revolution with counter-revolution; assuming that (if successful) one will provoke the other. And, perhaps tragic in itself, he was able to apply lessons from the French Revolution in ways we may now perhaps begin to approach the development of the Arab revolutions. Throughout this paper, I try to suggest how this dual-process is taking shape in Syria, with a particular lens on web and online political activism. This paper deals both with offline and online dynamics to reflect how, as in real life, both realities do in fact constitute a dialectical continuation.

Counter-Revolutions

A counterrevolution thriving on the Internet reflects how strongly cyber politics are embedded in the material reality of the Syrian revolution. Since a counter-revolution is the other side of the same coin, it can’t be any other way. Taking this as our starting point in a broader analysis firstly means that techno-determinist projections (whether dystopian lamentations or utopian celebrations) must be understood as overlooking the important manifestations of the impact of neoliberalism—including the unequal distribution of counter-revolutionary (surveillance) technology and overt and covert geopolitical interference which cumulatively result in a more circumscribed space for grassroots contestations. Placing the political outcomes in their proper material context contributes to a more critical deconstruction and political economy in part helps to challenge such conventional one-dimensional discourses, as I will show.

In order to fully understand how online activism and political communication is shaped we must also consider political motives, solidarity, and the on-the-ground struggle between competing groups. In early 2013, I asked Khalil who actively engaged in the Facebook and blog debates whether Syrian revolutionaries were more fractured at that time compared to at the start of the revolution.

Syrians are less unified than at the beginning of the revolution as a consequence of the harsh repression of the regime because of foreign intervention from all sides; also because the two main so-called Syrian opposition coalitions [e.g. group around Haytham Manna`, the Syrian National Coalition] do not represent much on the ground.

For Khalil, a unified coalition has to be an organic part and organizer of the resistance. Whether this is peaceful or armed is a secondary matter. Not playing this organic organizing role, or doing so only selectively, makes it unviable. But the issue (and fear) of geopolitical (imperial) intervention had become the most polarizing matter, which then more than any other impediment, seemed to delay the revolutionary progress on an international scale. I knew Khalil was trying to intervene in the debate with the anti-war left on this very issue. So I asked him to clarify how being supported as anti-Asad activists by other powers (however unsought or expressed as lip-service only) impacts their revolutionary mobilization.

Firstly, it does not affect my engagement. I still believe and will continue to believe in the right of this popular revolution against this criminal regime. The difference [with other Arab revolutions] is that we have to fight against more enemies: the Syrian regime, Iran, Russia, the Gulf, and the West. But the question of support of the West should be nuanced, as there is no real support, only vocal support. Meanwhile new laws make it harder to seek exile in the west. So this so-called "Western support" that is used against us by Stalinists, conspiracy theorists, nationalists, without even understanding the roots of the revolution, fits well with the regime [narrative] that uses it to taint the popular revolution.

Interviews such as these helped explain whether the pervasiveness of the Internet also reflected the increase of solidarity offline; whether the growing numbers of Syrian Internet users and the intensity with which Syria is discussed online would speak to novel spaces. More specifically (or in reverse), whether exporting the radical tone so frequently seen on the Internet often amplifying sectarian polarization—actually negatively impacts offline dynamics too. According to Khalil,

The Internet is not separated from [daily] reality, but whether it reflects the reality on the ground remains an important question. I think it depends: overall, the struggle on the ground has united the Syrian people; it does not only divide them. So, despite the rise of reactionary groups that are financed by the Gulf countries trying to change the character of this popular revolution into a sectarian war. The majority of the popular movement refuse sectarianism and continues its struggle to overthrow the regime in order to build a democratic society. In addition, the fact is that from the beginning the regime targets first and foremost democrats and seculars.

But even in the case where ordinary people are not drawn by sectarian sentiments, the truth is that the regime does not shy away from exploiting these social divisions. That is what the regime has started doing from the early days of dictatorship under Hafez al-Asad up until the last three years, emphasizing a particular sect/religion or by privileging certain communities in exchange for their loyalty. The revolutions have put a magnifying glass on these matters and the regime has then managed to cash in on some of these loyalties which turns out to be a tragic albeit successful investment.

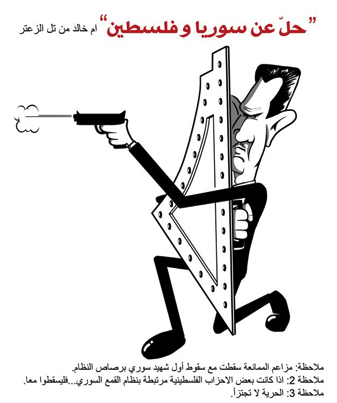

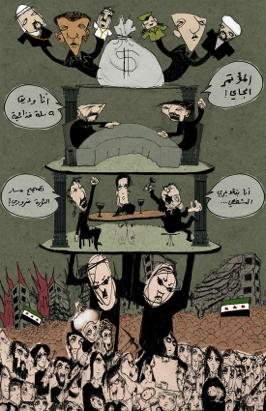

Beside such classic divide-and-rule mechanisms, another cynical tactic of the counter revolutionary strategies and tactics is deliberately utilizing historically sensitive and prescient issues such as the widespread support for Palestinian cause. Asad has managed to (as did Lebanon’s Hizballah) present itself as a key actor to Palestinian resistance and its quest for self-determination. Much of this discourse is taking place both online and in the mainstream media. Of course Palestine has routinely been used as a domestic shield for many Arab regimes. And especially in the context of Syria this tactic is replicated over and over, as expressed so vividly by graphic artists Amer Shomali in Palestine and Nidal El Khairy in Jordan in below images shared by many activist social networking pages.

These visual and artistic critiques are a tiny dot in the enormous online political consumption. But these important creative examples are unlikely in themselves however to tip the scale amid the whirlwind of aggressive content and the extremely loud pro-regime noises.

This means that while the widening public sphere offered by the Internet is important for Syria on a emotive level and for archival purposes (it is outside the scope of this essay to focus on this in detail as well but examples can be found elsewhere), it is almost by design simultaneously a shrinking public sphere. In other words, the Internet is as much a place to blame, silence, ridicule, or criminalize other voices as it is a place for sharing information. So far we have discussed counter-revolution in general and the online aspect thereof mainly as a discursive problem. For this reason I wish to shed light on the power structures that tend to favor the regime. I will take the analysis a few steps further and try to deconstruct the online aspect deeper.

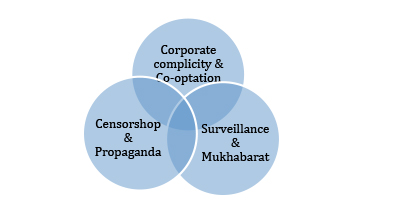

Concretely speaking, several counter-revolutionary fields can be identified that, whereas predominantly online structured, impede the Syrian uprising as a whole. Many of these are performed or prepared by Syria’s cyber army divisions and as a consequence disproportionately undermine pro-revolutionary activists. Since embarking on this research I have delineated three overarching counter-revolutionary contexts around which Syrian activists are obliged to maneuver—corporate complicity in terms of the co-optation of the ICT sector; state propaganda and media censorship; online adaption of the mukhabarat (secret service) through surveillance practices.

These approaches form three overlapping circles that together represent the oppressive sociotechno ecology of the activists. Putting it like this, we immediately get a view of the extremely convoluted struggle facing the Syrian revolution. I will now turn to reviewing the specifics of each of these contexts.

Corporate Complicity

Until recently it was considered counter-intuitive to castoff the celebratory theories of the Internet—existing hegemonic narratives were reinforced by popular notions such as ‘Twitter Revolution’ and ‘Facebook Revolution’ in the media. But we should note that the online opportunities of activists in themselves are mainly powerful relative to their economic and political resolves. Acknowledging this relation is partly a result of my adherence to Marx’s understanding of capitalist political-economy based on infinite competition and control over the means of production. This is even more so the case because in our current age global capitalism is the sum of many ICT companies. Such a perspective problematizes Internet activism, not with disregard for the impact of technology but with special regard to its historical materialist character.

The main corporate actors (including Google, Facebook, and Twitter) central to the production and dissemination of ICTs assume that the choices and motives pertain mainly to profit and private property will have important social implications. Hence, even if political-economy is not our first reflex when studying or using these tools, we need to start from the perspective that the technological aspects of the neoliberal sector first and foremost protect profit-based sales, irrespective of the end user, that is: if not on the contrary, where it even forecloses effective participation of the user.

For example, whereas major Internet corporations are often extremely protective of their content and intellectual property, social media is shaped by a peculiar preoccupation and urge to command consumer behavior, limiting the agency of the user. This is why they do not favor cultures of open-access and rarely share the algorithms embedded in their programs. Paradoxically, there is one partner the corporate world occasionally shares its content with and even swaps codes to strengthen the panoptic state. The major companies have systematically denied it but the US National Security Agency’s (NSA) own documents show that the US government has access to many company servers. In some cases telecom and Internet service provide (ISP) connectors who refuse state requests to spy on citizens may result in them being banned from the market. This means that, overall, only coincidentally and mostly indirectly, do their platforms and tools cater to activists. Microsoft’s search engine restricting search results for users in the Arab world has been documented with regards to obstructing gay and lesbian searches as well as other terms with a more political implication. And since 2013 we know that the surveillance of the Middle East has the highest occurrences.

Competition in the cyber warfare market is severe precisely because it involves big business, all parties want a share in the potential revenues even where there are direct adverse consequences for activists (Noman 2010; Youmans and York, 2012). This exists clearly in what we know about the lucrative distribution of counter-revolutionary Internet tools, Reporters Without Borders even named Blue Coat a corporate “enemy of the Internet”. Such systems continued to be sold because they use third parties in Europe or the Gulf and the Syrian authorities have reportedly installed more than thirty Blue Coat servers on their network since 2011.

Annual profits by companies such as US-based Hewlett Packard Co. and NetApp Inc. form computerized systems that monitor e-mail are rapidly growing (between three to five billion dollars in 2011). In an important investigative study, Citizen Lab has meticulously pictured a growing global market of surveillance software catering to state-sponsored espionage and data theft. Since the development of these products is no longer being undertaken exclusively by state agencies, the in-house, electronic intrusion capacities have moved to private companies, creating an even bigger market growth. These commercial interventions concern both national security and economic espionage and a greater number of cases involve hacking against activists. It has also been noticed that commercial companies (such as Advanced Middle East Systems) started to offer devices that directly tap fiber optic cables, raising even more concern among human rights groups.

After several attempts to raise public awareness (e.g., by Electronic Foundation Frontier) intermediary companies were eventually reprimanded for selling such devices to Syria. It has to be said however that the main motivation for abiding to the critique was not the extreme danger and therefore unethical practices these sales involve, but because they violate (US-imposed) sanctions against Syria. These are the same international sanctions that prevent activists from accessing many other tools and programs in their struggle, and which allow the regime to victimize it self and mobilize the public in its favor. This kind of complicity is merely the tip of the iceberg.

With the NSA data-mining story, the world learned of the outrageous activities of Prism. This changed the public’s view. The biggest companies in the field (Microsoft, Yahoo, Google, and Facebook) behave like virtual aristocrats; they have become cyber equivalents of proprietors, taking the liberty without consent to provide vast amounts of user data to government’s surveillance agencies and state-panoptic measures. Chelsea Manning, Edward Snowden, Glen Greenwald, and many more anonymous activists we have never heard of, broke these stories and their stories also signify that the struggle for transparency and accountability is closely tied to political justice. It also showed us just how interrelated capitalism and imperialism are in the world of technology in this particular context.

Geopolitical conflicts between states, exacerbated by political-economic motives (imperialism), has a particular connotation in the Middle East precisely because of the resources and the strategic locations it hosts. It has become even more relevant for Arab activists when geopolitical push and pull factors are represented by states that in fact also represent (host) the commercial ICT companies owning the networks that control online access to most of the online platforms. However indefensible it is not astonishing that large corporations work closely with security services be they the FBI, CIA, Pentagon, Shin bet, MI6, or one of the many Arab secret services. The negative impact of this logic inside the activists media environment is therefore more than the convergence of media platforms in a technical sense, but can be better understood using the term synchronization. Anne Alexander and myself discuss this elsewhere and suggest that the power of the media for activists is only relative to their power in other segments (class struggle, armed defense) of the uprisings. Yet, rather than simply being outraged, it is perhaps more relevant to recall that it is a product of capitalist mind-set, that this sector has consistently helped to maintain the capitalist status quo. Almost from its inception in Silicon Valley, these corporations became mouthpieces for a corporate ethos (Packer 2013) and willingly offered their assistance to the military industrial complex.

This is not so very different in Syria, which, despite its many other local and regional specificities (particular a kind of Arab-nationalism with state-capitalist characteristics), is a modern nation-state with pretty much the same capitalist push and pull factors. In fact, the key link in the counter-revolutionary progression of Syria is how the capitalist global IT sector follows its own assiduous logic here as well. The way the long arm of the state stretches out to the media sphere and telecommunication sector explains how corporate complicity can occur so ubiquitously in this context. Thus whereas corporate complicity and co-optation are global phenomena, the security services and ICT providers hampering the revolution in Syria is also of domestic nature. Yes, they use US products like Blue Coat, but they answer to their own superiors. This brings us to the next circle, cyber surveillance, where the counter-revolutionary socio-media ecology represents the mukhabarat’s deployment of strategies that obstructs activists’ abilities sharpest.

Online Mukhabarat

State propaganda practices and media disseminators are traditionally intimately connected, but especially so in our most recent digital era. According to Trottier and Lyon, the way subversive voices and political dissidents are banned or monitored online through state support is well documented. As mentioned, Israel serves as an exemplary case in which the state actively engages in the compulsive archiving of political resistance. In the last decade, this panoptic obsession was joined with monitoring Palestinian communication, mapping activists’ networks, and spreading online propaganda to discourage pro-Palestinian support (Aouragh 2013). The Syrian example comes to mind for its similar rhetorical, and even demagogic, style through which one can decode a comparable pattern, as I will mention in this section.

Since the revolutionary momentum picked up, the security branch of the secret service (mukhabarat) dealing with the Internet in Syria, popularly referred to as Branch 225 or the Syrian Electronic Army (SEA), has been working around the clock. It emerged in April 2011 around the time that Anonymous was very vocal and had started to hack official Syrian websites. One of the first acts of the section operating in what could be considered the hackers’ sphere was disabling Anonymous’ platform AnonPlus. The SEA is an interesting phenomenon as several have noted (cf. Baiazy 2012, Noman 2011, Fisher, & Keller 2011).

Challenging the myth of the good guys versus bad guys, hackers are active on both sides of the conflict in Syria. The SEA has its own YouTube channel on which it boasts about the websites it hacks or defaces by showing a Syrian flag or photo of Asad. The SEA is comfortably tied to the regime, it is unbothered by the fact that its domain name is registered inside the country with the Syrian Computer Society (an institute previously headed by Bashar al-Asad). According to Baiazy (2012), SEA has a Central Operations Room directly linked to the mukhabarat.

The need to step up, to “modernize” counter-revolution in the space where the opposition and dissidents were often found, lies behind the regime’s decision to lift the ban on some of the popular online platforms in several Arab countries during the events of 2011. The regime started to apply “Deep Packet Inspection” technology (such as the above mentioned Blue Coat) to study the individual browsing activities of Internet users. These new policies are mostly afforded to intercept communications and collect data circulated among activists.

Apart from regulating network traffic when needed, complete Internet cuts are not out of the question either. Through their liaisons they can blackout particular areas, often places where government forces (plan to) invade in order to cover up the deadly operations against civilians.

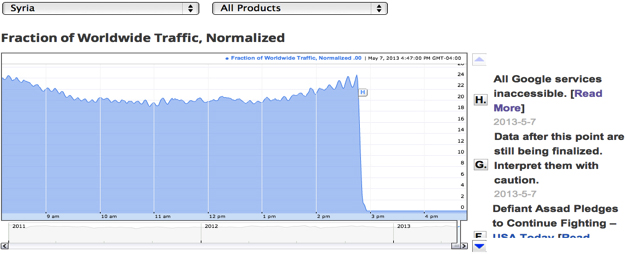

Renesys showed that all eighty-four of Syria’s IP addresses have been cut off several times (for example in November 2012 and May 2013), effectively removing the country from the global Internet pulse. The conditions have been extraordinary hard whilst on top of the people lost their usual means of communication. At that point some of the people of Baba Amr found no other means but homing pigeons in order to be able to send messages between the neighborhood’s that are under attack. In this poignant video young men receive a message from people under siege asking for gas and oil.

The online surveillance branches tied to the regime are mostly manned by young information technology (IT) students who are often assigned jobs at these task forces as part of their obligatory army service. The “Hacker from Aleppo” was initially recruited to work as a hacker for the regime as part of his mandatory military service. His online service would consist of tracking activists through social media, who could be imprisoned and tortured. In an interview on NPR Radio, he explained how he declined and then joined the revolution instead, where he did exactly opposite. Anti-regime activists have numerous defense mechanisms too, both technical and human. Harvesting, which amounts to hacking into the online accounts of anti-regime hacktivists as soon as they are arrested concerns the important task to wipe their digital footprints. They are an organic part of the revolution. Cleaning out online political profiles has been the specialty of the hacker from Aleppo.

This confirms that a serious component of the counter-revolutionary abilities is the work of the online mukhabarat. It can be a matter of life and death to remove incriminating content before SEA manage to analyze the online activities of the person arrested or by those in his or her networks. The secret service confiscate activists’ computers and, when necessary, torture against activists to force them to give up their passwords. They scan information or manage to recover deleted information (such as the deleting done by anti-regime hackers). The SEA improved further and spread their influence through acquiring/developing the capacity to tap into fibre optic channels and for instance tracing VoIP applications such as Viber and Tango used for audio (online telephone) communication. There are many well documented examples of the negative consequences (including the important work of Global Voices, EFF, and Digital Citizen) and the arrest of political bloggers like Hussein Ghrer and Razan Ghazzawi (more than once), as well as the kidnapping and disappearance of the well-known activist lawyer (the first to campaign for Syrian bloggers) Razan Zeitounah. These risks are very serious because as discussed in the previous section, these Syrian online mukhabarat branches have direct access to mobile phone companies, ISPs, and other operating communication systems in the country. This is giving them an advantage that is hard to keep up with. The last example is perhaps the most illustrative in terms of the predominance on the representational level.

Online Propaganda and Censorship

After the initial uprisings in Homs and other rebellious places saw brutal retaliations from the regime. State media and spokespeople of the regime routinely claimed that stories and videos were staged. It started also to release taped "confessions" claiming these rebels were paid by foreign powers. The need thus arose to move the counter-revolutionary propaganda and campaigns to online spaces—and to make efficient use of online surveillance methods—thus revealing the regime’s motive to accommodate such on line platforms as Facebook and YouTube.

In the previous section I mentioned how earlier work on Israel’s decision to allow the Internet during the outbreak of the Second Intifada (2000-2005), shed light on the comparable models by both countries. It is intriguing because the Syrian actions are very similar to the propaganda campaigns organized by its nemesis. The way Israel (and its supporters) exerted their efforts, as a form of online politics with their hasbara campaigns was a cue in formulating the counter-revolutionary public sphere of Syria and the regime’s subsequent intervention in creating this.

Counter-revolutionary content has rapidly increased on social media since 2011. Preliminary data showed more pro-revolutionary Facebook groups and tweets (approximately 3 to 1 from our collection of around 300 pages). Instead of a pro-anti hyperbole, or at least a recurring "war of words," that we expected when we looked into the social networking sites, there seemed no authentic interaction between what can be considered pro and anti revolution Facebook groups. This indicates that the “echo-chamber” phenomenon that has typically characterized the political blogosphere also thrives on social media, and challenges any potential notion that the Internet per se unites opposing groups. Our analysis of Facebook groups in April and again in September did suggest that the drums of war grew louder and we noticed an expressed conviction in support of the Syrian regime both in language and visual representation. One example is the image of Asad forces booting down opposition rebels, demonstrating a self-confidence that was quite pervasive.

A tight control on the media is legitimated by Syria’s prerogative of a state of emergency, which in turn is given credibility by the behavior of the so-called "pro-United States" axis (rival of the so-called ‘pro-Iran’ axis). This configuration thus allows the regime to exploit its pro-resistance and anti-imperialist credentials. But while anti-Asad foreign states verbally support the revolution they are not the allies of the revolutionaries for they effectively marginalize Syrian dissent. This adds to existing confusions in terms of who to support, whether offline or online and in essence help provide coverage for the counter-revolution.

It is fascinating to see pro-regime groups mimicking revolutionary groups such as pro-Asad Facebook groups using similar sounding names (e.g., Syrian Revolution). Also from data collected via R-Shief, it turned out that the general “Syria” or “Asad” hashtags were easy to confuse for pro-revolutionary references, and mistakenly assumed to reflect activist discourses. These are not coincidental mistakes. Instead, this is part of a deceptive tactic by regime propagandists to lure viewers as also occurs on other news mediums. The appropriation of url names by hasbara groups comes immediately to mind. We noticed a divide between domestic and international mobilization on Twitter. Outside Syria, the primary tendency of what can be called the Syrian hasbara was based on the objective to feed journalists or politicians narratives that were the regimes’ versions of events, what seemed like a state orchestrated public opinion.

In fact, there is one more important similarity. In order to negate Palestinian rights, a core component of pro-Israeli hasbara is the employment of “guilt-by-association” (the underlying label being anti-Semitism because the "association" is Palestine also meaning anti-Israel and through a nasty extension in hasbara logic means anti-Jewish). Conversely, Syrian regime propaganda benefits by exploiting sympathy for Palestine and the moral question of justice related to Palestine.

The benefits of such emotionally charged politics can be achieved by simply replacing a Palestinian flag with an Israeli one, photoshopping it, then spreading it online so as to smear those who are protesting against the Syrian regime. The photoshopped image here is one that I found on my own Facebook newsfeed, which although it looked strange still suggested Syrians carried Israeli flags. But not long before I had seen protests of Palestinians from Yarmouk refugee camp in Damascus and Syrians against the Syrian regime and I realized it was the same occasion, otherwise I would not have known that the original Palestinian flag was erased and then replaced with an Israeli one in order to make the claim that anti-Bashar al-Asad protesters are Zionists.

The reason it works better in the Syrian case than in the Israeli attempts against Palestinians, is related to the fact that pro-Syrian regime activists are organically rooted in the counter-revolution. They have been so from the start and it is certainly much more supported than one would wish. Unlike other online diplomacy efforts or propaganda trolls, they rely on very similar historical narratives and references, albeit operating for opposing goals: committed volunteers with opposing political convictions who share a similar cultural language and demography. It is less artificial than one would expect. That is why it comes across much more natural on social networking sites: they are not as ‘artificial’ as for example paid volunteers tend to come across. And this is not uncommon in the complex reality of political alignments and Ba`athist secular constructions of Arab "modernity." This resonates in a sense with what Donatella Della Ratta observed in the television and movie making milieus where there is an elective affinity that binds Syrian cultural (here television drama makers) producers and the political elite around Bashar al-Asad. They simply do not see a principle contradiction in their alignment with a violent regime and their "progressive" ideals and their vision actually reflects that of the president rather than independent dissent cultural producers one would expect from an intellectual milieu.

With the increasing volume and presence of counter-revolutionary politics and sectarian divides it almost becomes an aspiration in itself to push against a divisive social separation. Long periods of violence can have a tendency to traumatize and therefore anesthetize people. This has become one of the additional impetuses behind Syrian activists’ use of the Internet to share and promote revolutionary efforts. And here we see that online spaces of interaction and mediation are no tabula rasa but carry a legacy.

The fact that Syria’s earlier blogosphere was weaker contributed to the unequal socio-political balance of forces. Due to the dictatorial methods and the anti-imperial blackmail reactions, the social movement could not congeal. It could not become as vibrant or fixed as elsewhere. In turn, the blogosphere was not afforded a chance to grow and mature in its own pace and terms. Consequently, it was less united (for instance compared to Egypt) against the government. But the lack of an organically linked network on the ground also meant critics from civil society and the blogosphere were not catapulted into the movements, such as what happened around well-known internet celebrities in Egypt that were part of the April 6 Movement and the Tahrir uprising. And this matters because having an independent political trajectory (that is linked both online and offline) generates familiarity, and in turn, trust and we could add: protection. As illustrated so vividly by Hussein Ghrer, just before he was arrested in February 2012 (120):

It pained us not to be able to play the same role in Syria, as conditions there were completely different from those in Egypt. We, the bloggers and the old activists, so to speak, had to lie low as bloggers so as not to expose our identities.

He then takes us a step further and specifies how bloggers were unable to play a major role in the revolution because “[E]ven those who participated in the protests and were arrested could not post the news of these protests using their real names or write their own personal accounts.” This reflects an important local dynamic, one with a paradoxical reality that challenges many of the dichotomous readings of cyber activism. It is a public and private sphere in which pro- and anti-regime bloggers, and activists are present, in the same online spaces, and that occupy the same sites of resistance.

All in all, the deepening polarization inside and outside Syria is reflected by the network of bloggers and Internet activists previously involved in political campaigns. Syria did have political bloggers and they were known for their outspokenness. It was somewhat unexpected that they would become divided on Asad. Though, again, Hussein shares his views about his own thoughts as a blogger at the time. “While some bloggers sided with the Syrian regime in confronting its people under many pretexts, the majority of bloggers supported the revolution fully from day one.” This is ultimately why those who knew each other personally wondered about their absence in the Syrian revolution. Moreover, it was becoming too dangerous and adaptations were necessary. Bloggers living in Syria could not openly announce their support of the people’s demands through their blogs either, there was “[F]ear of arrest or maltreatment by the security forces. And the same went for some bloggers abroad who feared for their families in Syria.”

Although we examined how many members the counter-revolutionary Facebook groups had it occurred to us that they were not as strongly and creatively present as the pro-revolutionary groups. But it was still relatively high and their tone was confident and approach resolute. Where Facebook disabled several SEA pages, they were replaced almost immediately by others that popped up in their place.

This form of activity is, on a global scale, more prevalent because (like the domestic political spaces) the online spaces of the international activist community are also split between pro and anti-revolutionaries. The threat of imperialism is calculated by different sections of the movement in different ways. Syrian counter-revolutionaries can also count on silence if not the support of activists for example from Palestine, Lebanon, Morocco. A painful example were the clashes between pro- and anti-Asad groups at the World Social Forum in Tunisia in 2012, and also the dispute among different Palestinian groups discussing how to formulate a principled position about the violence (especially vis-à-vis Palestinian refugees) in Syria earlier this year tells us that the question is far from unanimous. But actually, this is not very surprising if we remember the appeal of the Syrian state’s anti-imperialism (even if just a smokescreen) that has had resonance with a section of the left. This perspective may appeal to an older segment or to those consumed by third-world politics and seeing the struggle mostly through the lens of anti-imperialism. But this prism has nonetheless divided the political forces in many Arab countries. Anti-regime activists are at best seen as an unfortunate cog in a wheel and at worst as pawns in a regional game of chess. Syrian pro-democracy activists are endowed with very little agency.

Conclusion

It is very possible to have a "Facebook Revolution" and a "Facebook Counter-revolution" together at once. It is not enough to challenge the dichotomy in the techno frameworks only. An approach to revolution as inhibiting counter-revolutionary "challenges" necessarily assume that counter-revolutionaries active in cyberspace are not following orders per-se, they are not only on the payroll of the SEA. The counter-revolutionary groups therefore use state and military symbols in their online profiles (donned with Russian MIG, portraits of Bashar al-Asad himself in military costume, and the flag of the Ba`ath Party) and anti-Israel rhetoric. Such digital gear (profile pictures and hashtags) absolves the regime of responsibility and accountability.

We need to consider an online (techno) mobilizing struggle and a physical confrontational struggle at the same time. This dialectical approach will allow us to avoid the trap of seeing results mainly through technical solutions instead of (first and foremost) how they (relate to) resist the systemic bases of oppression itself.

Besides flooding, jamming, and occasional hacking, the primary means of online counter-revolution as a form of cyber warfare in Syria concerns surveillance and propaganda. On the one hand the work of Syrian hackers help demystify the prevailing myths about hackers that are constantly portrayed as Western geeks that "help" others around the world. But their activism, described in this paper as extremely aware of the unequal balance of forces, also clears away the mythology of Internet-enabled revolutions, this will at least save new activists much frustration and prevent unnecessary disappointment.

Moreover, the continued ambivalence (and genuine fear) about the consequences when the regimes falls and outside powers intervening, allows Bashar al-Asad to evoke anti-imperial sentiments. I described how in the area of surveillance much of the important work revolves around assignments of responsibilities in the context of (military) conscription. But later in the paper, when discussing the broader field of propaganda, is has become clear that pro-regime interlocutors are behaving also from a self-chosen commitment from a notion that they are doing the right thing. In such an enigmatic state, opposition groups are automatically tainted their interests are pictured as meeting those of external geopolitical forces, even when that is an undesired juncture it allows Asad to parasitically prolong his reign. The online counter-revolutionary space functions as a parallel political space, which is not ethical or representative. But it is not merely "virtual" because by simulating a reality—and embellishing it—it contributes to the unequal balance of forces with very material consequences.

-----------------------------------

Notes

[1] This is more than a cynical plot, it also is more susceptible because of the risky outcomes these regional reshuffles have for Palestine. And it is a genuine concern because of the organic affinities in many third-world/colonial contexts, rather than a distinct nationalist project. In other words, it works as a negative fig leaf because of a positive historical sense of Palestine being part of a collective cause.

[2] For Their Eyes Only: The Commercialization of Digital Spying. By Morgan Marquis-Boire, Bill Marczak, Claudio Guarnieri & John Scott-Railton. Citizen Lab. Available online:

https://citizenlab.org/storage/finfisher/final/fortheireyesonly.pdf.

[3] <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/nov/18/private-firms-mass-surveillance-technologies>.

[4] Many of which are irrelevant random American or French targets.

[5] Renesys is a group of analysts that monitor mobile and Internet connections.

[6] Eventually he had to flee Aleppo like many others. He continued his hacktivism and one of his projects is building a scoop-robot—a computer-controlled device with titanium arms on wheels that is meant to pull away the fatal targets of snipers. The aim is not only to rescue wounded Syrians, but also to save more lives, because as he observed, the army started to apply the classic tactic of wounding one and then killing more people that rush to the rescue using snipers.

[7] This is ‘manual` analysis was done by Khadija Dermame and Miriyam Aouragh in 2013.

[8] That is, apart from Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism explaining part of the success of the Zionist lobby.